Posting pictures from Bergamo is really damaging to my cachet with my Dreaming Spires students, who expect me to devote all my love to the Romans and Athenians. There is a case for saying that the oldest parts of Bergamo, and many ancient Italian cities, are a better way of understanding the experience of walking a Roman street than any ancient site, with added ice cream.

In this very photo, we are only steps from the best ice cream in the Città Alta, the UPper City, but more importantly we are near the Civic Archaeological Museum of Bergamo, which is where the small but very interesting collection of Roman period remains is beautifully curated. Photography is not encouraged, but I seem to have accidentally clicked my phone a couple of times while checking Whatsapp.

Bergamo was a city before the Roman era. Northern Italy, to the Romans, was not part of Italia, but Gallia – they called it Gallia Cisalpina, Gaul on this side of the Alps. This was a tribal area, and Bergomum was a hill town of the Cenomani. The Piazza in the photograph is on a high point which may have been the original citadel, as the name suggests; in the 14th Century, a new fortress was built on a spur and this became the citadel. The Romans called at least some of the Gauls ‘Celts’ and this has misleadingly become a term for Iron Age people in general. The Cenomani didn’t call themselves Celts. Livy records that the Cenomani had moved into Italy from France in about 400 BC, seizing and occupying Etruscan territory. They probably spoke a dialect of a language we call Celtic, and definitely didn’t speak Latin at that time.

In the 5th Century BC, Rome was still a minor power within Italy. In about 390 BC a Gallic tribe, the Senones, even sacked Rome. The Cenomani, however, were actively pro-Roman, and fought on the Roman side in the major Roman victory over hostile Gallic tribes at the Battle of Telamon in 225 BC. This battle ended the threat from the North, although Cisalpine Gaul was not formally organised into a province until 89 BC. The Cenomani, remained loyal even during Hannibal’s invasion of Italy (218-204 BC). Bergomum was granted full rights a Roman municipium in 45 BC, making citizens of the town full Roman citizens. Shortly afterwards, in 42 BC, Julius Caesar extended Roman citizenship to the whole of Cisalpine Gaul. The Bergamasks were now Romans.

The Cisalpine ‘tribal’ peoples on the edges of Rome’s growing Italian empire were not very different from the people within it. The Romans themselves were tribally ‘Latins’ who developed an empire, first of all over all local cities and then elsewhere. Even before the rise of Rome, the Northern Italians were living alongside the Etruscan empire, with its advanced social organisation, art and technology. The Cisalpine Gauls used writing – hardly any survives – and made fine metalwork. In the long period of cooperation between the Cenomani and Rome, there must have been a lot of cultural absorption and the number of Roman citizens in the territory will have increased both through migration and grants of citizenship to soldiers and the local nobility. By the time Julius Caesar extended Roman citizenship to them, teh Cisalpine Gauls were integrated into Italian identity, and Latin was the language of the educated class.

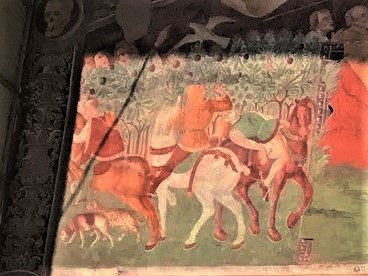

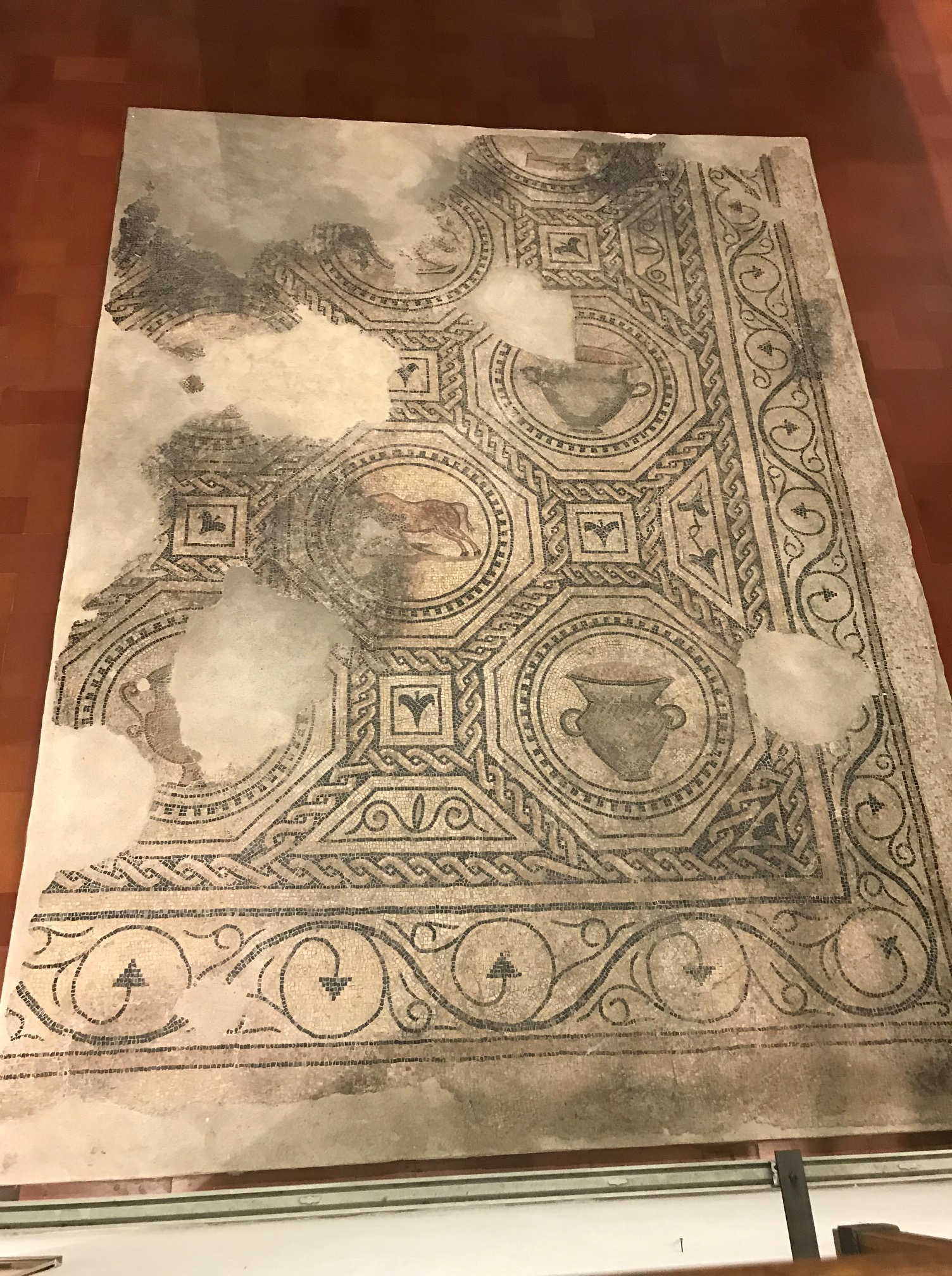

The Upper City of Bergamo is largely on top of Bergomum. The stones of the Roman period buildings are holding up the houses and Churches visible today. This makes the modern environment very rich, but it does limit the archaeology. If you want to find a nice Roman carpet mosaic, then the best place to look for it it is in a field, which has been grazed on by cows for two millennia. A place which has been developed and redeveloped again and again AND IS STILL BEING LIVED IN is not the obvious place to start wielding a trowel. But having said that, here is a carpet mosaic from Bergamo.

And here is an altar of Diana with a beautifully clear inscription.

The distinguished man (CV = Clarissimus Vir) who set it up in fulfilment of his vow (VS = Votum Solvit) was consul in 201 AD, when the consulship had become more of an honour than an actual job. Titles like Clarissimus Vir aren’t used on formal inscriptions from the Republic and Early Empire, but in the second century AD this becomes a standardised title for a Senator. The use of formal honorific titles grows in the later Empire and grade inflation even sets in, until a really important official has to be a Vir Gloriosissimus. In early Latin literature gloriosus means boastful, not glorious, which is quite pleasing.

This amazing bull’s head was part of a set of ornamental beam ends in the Roman theatre. The strange creature on the side will resolve itself into a dolphin if you concentrate. Dolphins were associated with Delphi and Apollo, God of Poetic Arts and the Romans tend to make dolphin beaks very big. My guess is that this came from people who hadn’t seen dolphins in non-dolphinous places like Bergamo copying popular motifs from drawings, but what do I know? Bulls are associated with festive occasions as sacrificial victims, aka lunch. Roman theatres were not commercial and did not have regular showings. They were used for a variety of civic events, and theatrical performances were staged on holidays with the sponsorship of high-ranking locals who took care to get maximum publicity for their generosity.

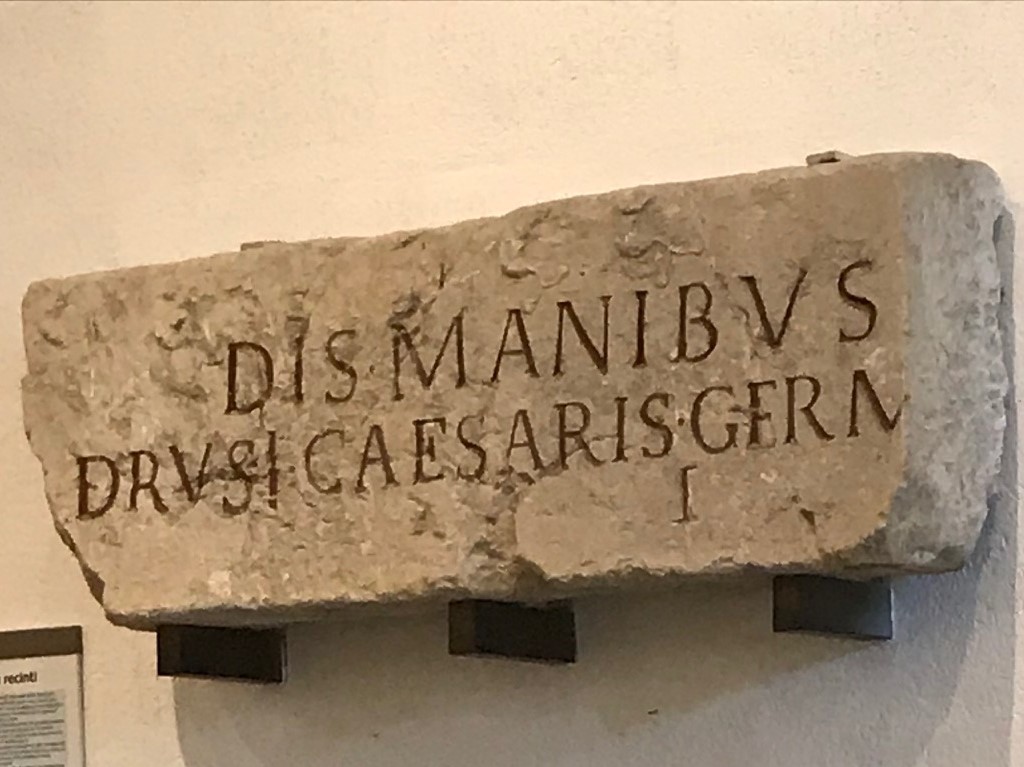

And finally, something which ties in with my posts on Germanicus, nephew of the wicked Emperor Tiberius, who was murdered in AD 19. He was an important member of the imperial house, and the founder of the dynasty, the Emperor Augustus, had intended Tiberius to be a caretaker ruler only. After Tiberius, Germanicus would take over, and the dynasty would pass on through his numerous heirs. In reality Tiberius clung onto power until 37 AD, more than a decade after the death of his own son, and nearly two after the death of Germanicus. His successor was Caligula, youngest son of Germanicus, and one of the most notorious emperors; the experience of having his father murdered and mother and older brothers openly persecuted to death by Tiberius may have contributed to his instability. All of this was court politics, recorded in vicious detail by Tacitus. But these fractures in the imperial house were not public property. Bergamo is 400 miles form Rome. Like other cities of the Empire, Bergamo culted the Emperor and the imperial house and monumentalised its members as the embodiment of Roman authority. Up and down the empire, cities commemorated the death of Germanicus with plaques, honouring the wish of the Emperor, who, Germanicus believed, had ordered his horrible death, and who certainly went on to wipe out his family. Here is Bergamo’s effort.

Actually, that is a bit grim to finish on. Here is a nice picture of exceptionally yummy nibbles and non-alcoholic beverages in Clusone, being investigated by my research assistants.

And here am I, smiling at you. Hey students, don’t forget to sign up. This year there’s The Making of Fifth Century Athens and New Testament Language and Culture. I’m also working on a GCSE Classical Civilisation course for 2020. Hope to see some of you there.

Bye.