It is very risky to talk about ‘witchcraft’ at all. It means so many different things to different people. Everything I write is based on things in my library and I going to look at a passage of Tacitus and use it to explore practices within Roman culture which later scholars call ‘witchcraft’. So don’t expect anything about Wiccanism, Satanism, coven witches and many other things commonly associated with the term ‘witchcraft’. I am going to write about the Roman belief that people could exercise power over others by indirect and non-rational means, which we would call ‘magical’. The Romans seem to have regarded this sort of practice as a common source of harm. In their literature, practitioners are always regarded as dangerous, but their criminal law legislated against particular ‘magical’ crimes, not being a ‘witch’. At the end of the post I will ask how appropriate the Anglo-Saxon term ‘witchcraft’ is.

Roman practitioners of these disapproved arts invoked gods and spirits, but in ways condemned by the community. Their behaviour was distinguished from the good and proper relations with the gods, which the Romans called religio or religion, although there was an overlap. The gods of the upper world were associated with light and life and had nothing to do with the pollution of death. Everyday petitionary prayers went to them. The dreaded underworld gods were associated with death, misery and darkness and their worship involved nocturnal rituals and the sacrifice of black animals and even the sacrifice of dogs – unclean for normal sacrifice. But all this was part of normal religion – the gods concerned with both light and dark deserved their dues.

We only enter the realm of evil when engagement with the underworld deities moves from the community propitiating them in the proper ways to individuals calling upon Hecate, Dis and infernal spirits secretly and harnessing their power to evil ends, especially towards causing sickness and death. The Roman sources tell of forbidden and polluting rites, carried out at night, and including the desecration of dead bodies. Practitioners were supposed to use harmful incantations. They also made potions and objects which gave them special powers, especially control over others. The sources have to be used with caution, but there is strong evidence that these practices did actually exist. Practitioners were not regarded as having an alternative religion – instead they had illicit commerce with the gods of the religion of the community.

The Latin word we usually translate as ‘witchcraft’ is maleficium – harm-doing, a word which could also be used of harm in general. Practitioners were malefici ( female maleficae = harm-doers). Rome’s oldest laws the Twelve Tables, exist only in fragments but seem to have included, with other crimes against persons and property, enchanting by an ‘evil song’ (malum carmen) and removing crops by enchantment, again by song (qui fruges excantassit). The references come from Table VIII 1b; 8a quoted in Pliny NH 28. 4). Later legislation follows the same pattern and specifies the banned ‘magical’ practices without distinction, alongside other forms of harm, such as arson and stabbing. The Romans did not call these practices ‘magic’. The Latin word magia from which we get ‘magic’ meant something also suspect, but different from maleficium, namely astrology. In legal texts, the key indicator that we are talking about ‘magical’ harm is usually the association of harm with singing in some way – particularly the malum cantum, the ‘evil song’. But this is misleading, as we shall see below. Mentioning ‘evil singing’ identifies the kind of harm that is going on, but Romans assumed that it would be accompanied by a other acts from a wide range of options, including, at the least, ritual activity while the song was sung.

Returning to Germanicus, this magical indirect harm-doing was strongly associated with an undoubted way of doing criminal harm at a distance – poisoning. A poison is definitely a potion which gives you control over others. The Romans did have a concept of poison (venenum) as separate from other malefica (‘magical’ harm-doing things), as the passage below shows, but in the absence of advanced chemistry, it made perfect sense to reinforce the drug with occult methods, which may have gone even into its preparation. It is not surprising that people adept in poisoning were expected to be adept in other forms of harm at a distance. Tacitus account of the death of Germanicus is good evidence of the inseparability of poisoning and maleficium in the Roman mind. It also shows the sort of harm-working things (malefica) which would accompany the evil song.

The first symptom of poisoning is, obviously, serious and sudden illness. In the ancient world allegations of poisoning almost invariably accompanied the sudden death of significant figures. Tacitus likes to cite evidence. Here he notes Germanicus’ own belief and the curiosity of Piso as circumstantial evidence. But he also cites as supporting evidence for Germanicus’ belief a bizarre array of nasty objects hidden in the house where Germanicus died. These, it seems, are the sort of things which may accompany a poisoning. Tacitus refers to these briefly, because they are well known (in popular belief) and even leaves some for the reader to supply. He calls the cursing objects collectively malefica – ‘harm-working things’. Tacitus’ lack of surprise and his assumption that the reader can supply the details of other horrors is extremely interesting – in his Roman mind these bizarre proceedings are a familiar modus operandi.

So what are the malefica? The human remains look like graveyard pilferings – a common accusation against ‘harm-workers’, and a serious assault on the safety of the dead. The cinders combined with gore (tabo) come specifically from the cremation grounds. Human remains were polluting in the Roman world. Prayers to the upper world gods could not be made in their presence, and so the objects must have compromised the religious safety of Germanicus’ household. There may also be an attempt to make Germanicus dead by bringing him into contact with the dead. Below, we shall see this in the case of a different spell. But it would not be irrational to suppose that polluting a house with human remains would also cause illness. The finding of the objects concealed in walls and floor is suggestive. Did Romans often look for malefica in case of sudden illness? Or did the objects leak and smell? Did someone know where to look for them? Were they meant to be found?

The Latin Tacitus uses for ‘incantations and spells’ is carmina et devotiones. We have met the malum carmen (plural carmina), the ‘evil song’ as the key ingredient of maleficium. Clearly there might be literal singing, but in this passage of Tacitus we see that writing charms down and placing them in contact with the victim was effective too. Writing was a powerful vehicle; you could harm your victim both by placing harmful words in your victim’s presence, and by capturing your victim’s name and using it in harmful ways. And of course, with this kind of access to the victim, harm-workers could support the carmina lavishly with other malefica, and help the spell along with physical means, like poison.

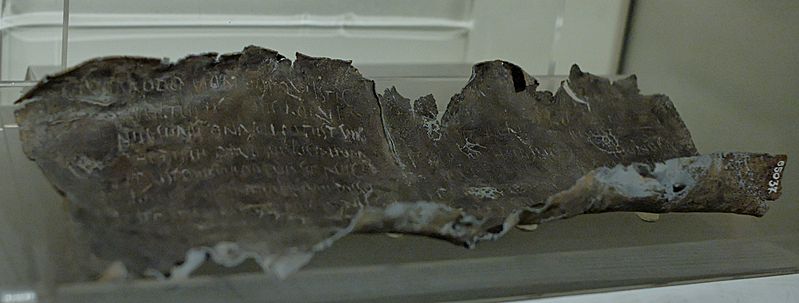

The reference to leaden cursing tablets, defixiones, can be supported from archaeology. We find cursing tablets deposited by people with grievances in sacred places – usually in water, but, of course, ones thrown into water are preserved best. The defixio, sometimes in backwards writing, encourages the deity of the shrine to punish the enemy. Seen by itself, placing defixiones in shrines could be no more than an emphatic form of negative prayer. It hardly required secret knowledge. The gods of the dead were not invoked over the affairs of the living – a transgressive feature of maleficium. There was, at face value, no malum carmen, although we cannot know what rituals may have accompanied the defixio. The physical tablet may only be part of the story, as it is in Tacitus.

Tacitus also mentions devotiones. The defixio above looks fairly typical. But it is different because of its content and its location – it was found in a graveyard and contains a special form of curse – the devotio – which offers possession of the victim to underworld spirits.. On the tablet Marcus Licinius Faustus consigns Rhodine and several other people to Dis, god of the underworld. Gifting power over the living to the gods of the dead is something more than a common defixio and it is noticeable that Tacitus makes a distinction.

In certain circumstances, a devotio could be a good thing. Livy (8.9) records the battlefield devotio of the consul Publius Decius Mus in 340 BC. Decius, according to Livy, sought the approval of the pontifex maximus, the highest religious authority, before dedicating himself and the enemy army to Earth and the underworld spirits. He then launced himself suicidally against enemy. He was rewarded with Roman victory and everlasting fame. But this was an open and self-sacrificing act for the benefit of the community at a place of slaughter, where the underworld spirits were already active.

Marcus Licinius Faustus’ act is the opposite – it is secret and selfish and involves desecrating a grave, presumably by night. Graveyard rituals and desecrations are strongly associated with maleficium and maleficae in the sources. It seems that Marcus Licinius Faustus has crossed the line. As in Germanicus’ case, he brings the victim, or at least her name, into contact with the dead: he writes [may she] have as much strength as the dead man who is buried here. It would be interesting to know whether he performed other graveyard rituals which leave no trace.

Tacitus’ account shows cursing tablets could be left in the victim’s home as well as in sacred places – something we would be unlikely to find out by archaeology. We are now developing a picture which suggests the Romans mentally expanded the ‘evil song’ of the Twelve Tables into a complex bundle of acts, including physical attacks on the victim’s home. Was placing cursing tablets in the house supposed to be magically effective, or were they primarily intended to signal to the victim that he was under occult attack ? They did in fact signal that an enemy had access to the house. Would curses against Germanicus also have been placed outside his home, in graves or shrines, or are we looking at variation in practice? Did Marcus Licinius Faustus try to invade Rhodine’s home as well as working his graveyard ritual?

How did all these malefica, ‘harm-working objects’, get into Germanicus’ house? The Roman slavery system made hostile infiltration fairly easy. The agents in other poisoning cases are said to be slaves controlled by the poisoner. Were the objects meant to be found? Certainly Tacitus claims Germanicus’ illness was increased by his terror. In this case, if Germanicus was poisoned, the rational and irrational methods of causing harm at a distance were worked together to produce greater harm than poisoning alone. So perhaps Roman maleficium was effective on a psychological level, as magic is said to be in many parts of the world even today. Tacitus claims the forms of malefica he describes were well known and, in Germanicus’ case, the practitioners were rewarded with practical results. His illness was increased by terror, and, as a bonus, he died in an agony of despair.

Why and how these bundles of actions produced their effects could not be resolved until there had been another thousand years of scientific development. So the Roman law makers were probably being pragmatic when they identified indirect harm-doing (maleficium) by the ‘evil song’, the malum carmen, as a crime. We are looking at a society where people in general including those with criminal intent believed in the power of ritual actions. Rituals and the ‘evil song’ were part of the toolkit for practical efforts to control and even kill others. And although the agent worked at a distance from the victim, we have seen that physical contamination of the victim’s home could be part of the method.

Well, what about ‘good witchcraft’? This doesn’t really exist as a concept when scholars talk about Rome, because what we are translating as ‘witchcraft’ is maleficium – ‘harm-doing’. Good-doing, by whatever means, including acceptable ritual practices and invocation of spirits, just wasn’t a problem. Songs, including sung charms are all called carmina in Latin. The only kind of carmen worth worrying about was the malum carmen, the ‘evil song’, which was dangerous and illegal. Such songs could cause death, although death wasn’t the only objective of the ‘evil song’. Love charms too could be reinforced with a drugs and ritual actions. The surviving literary examples – Theocritus Idyll 3 and Virgil’s Eclogue 8 – envisage the love charm as vengeful and coercive. The Twelve Tables mentions enchanting crops – clearly a big concern. This suggests a hinterland of persecuting vulnerable people for crop failure, but given our practical evidence for maleficium we have to tread carefully. Unless you believe in ‘magic’, it is hard to see how any form of spell could damage crops, but threatening or offering to do so could be criminally profitable. And, as we have seen, your spell might be helped along with physical action.

The Roman believed in other kinds of charms. In Apuleius’ Golden Ass, the hero accidentally transforms himself into a donkey. He has got hold of a powerful spell, belonging to a dangerous practitioner of spells, who is able to fly, but it is only harmful to him because he is an idiot – an ass, in fact. Benign singing and ritual directed at objectives like fertility and prosperity merged into religion. And benign making of ritual objects and potions for healing merged into medicine, which included non-rational elements at Rome. Sometimes it is hard to decide whether singing practices are ‘magical’ or not: is a lullaby a sleep charm?

You could say that ‘magical’ ways of doing things were integral to Roman culture. No public business could be done without examining the sky for signs. Omens could hold up battles, ritual mistakes could cause enterprises to be abandoned. There was no stable way of disentangling rational and irrational practices. There were particular harmful ‘magical’ practices which were distinguished and condemned, like harmful non-magical practices; to the Romans they were all just harmful practices. Roman ‘witchcraft’, or what we call Roman ‘witchcraft’, is, by definition, always antisocial.

So is ‘witchcraft’ the correct word? English speakers are stuck with it because of two thousand years of discourse about ‘magical’ practices, which led to whatever it is the Anglo-Saxons meant by ‘witchcraft’ being identified with a combined package consisting of what the Romans called maleficium and other practices which had come into official disrepute by the beginning of the modern era. These included benevolent charm and potion, which were increasingly excluded from legitimate medicine. It didn’t help that the Old Testament (Exodus 22.18) condemned ‘witches’ to death – or at least, it did once it was translated accessibly into English in the sixteenth century. Who exactly was condemned to death in the original Hebrew is hard to say – but the intended target may have included poisoners, something we can easily understand from the Germanicus story. There is an online article about this here.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were an Information Age, as movable type and the Renaissance rediscovery of the Classics widened both the spheres of learning and the availability of books. Society was moving towards the twin system of science (the accepted rational) and religion (the accepted irrational) which is familiar today. This binary system excluded and marginalised all practices not sanctioned either by scholars or priests. Classical education only reinforced concerns about ‘witches’ with solid Roman authority and horrifying anecdote. Reports of cultural practices from a range of societies, and going back 2,000 years, gathered in libraries to form the basis of a pseudo-science of ‘witches’ with enthusiasts including James I of England. ‘Witchcraft’ came to be viewed as a single phenomenon stretching across time and place, with a set profile of inter-linked occult behaviours which now also included obedience to the Devil. Someone suspected of being a ‘witch’, on any ground, was likely be tortured into confessing other acts from the profile, like flying and devil worship, which as a ‘witch’ she (because women were most suspected) must surely commit. The seventeenth century became an age where women in England could be hanged, essentially, for having a cat.

‘Witchcraft’ charges have become notorious as a pretext for misogyny, religious persecution and various sorts of abusive and disempowering misbehaviour. We even have the phrase ‘witch hunt’ to denote meaningless persecution. Tacitus’ account of Germanicus’ death reminds us that in the pre-modern world, certain sorts of ‘magical’ practice were criminally intended, and were supported by forms of physical intimidation still criminal today. In the popular perception, and it seems, at least occasionally, in actual fact, these practices were linked to poisoning. They were associated with terror, physical harm and death. The death of Germanicus gives us an idea of what the ‘evil song’ might look in practice and why it was illegal in Roman law.